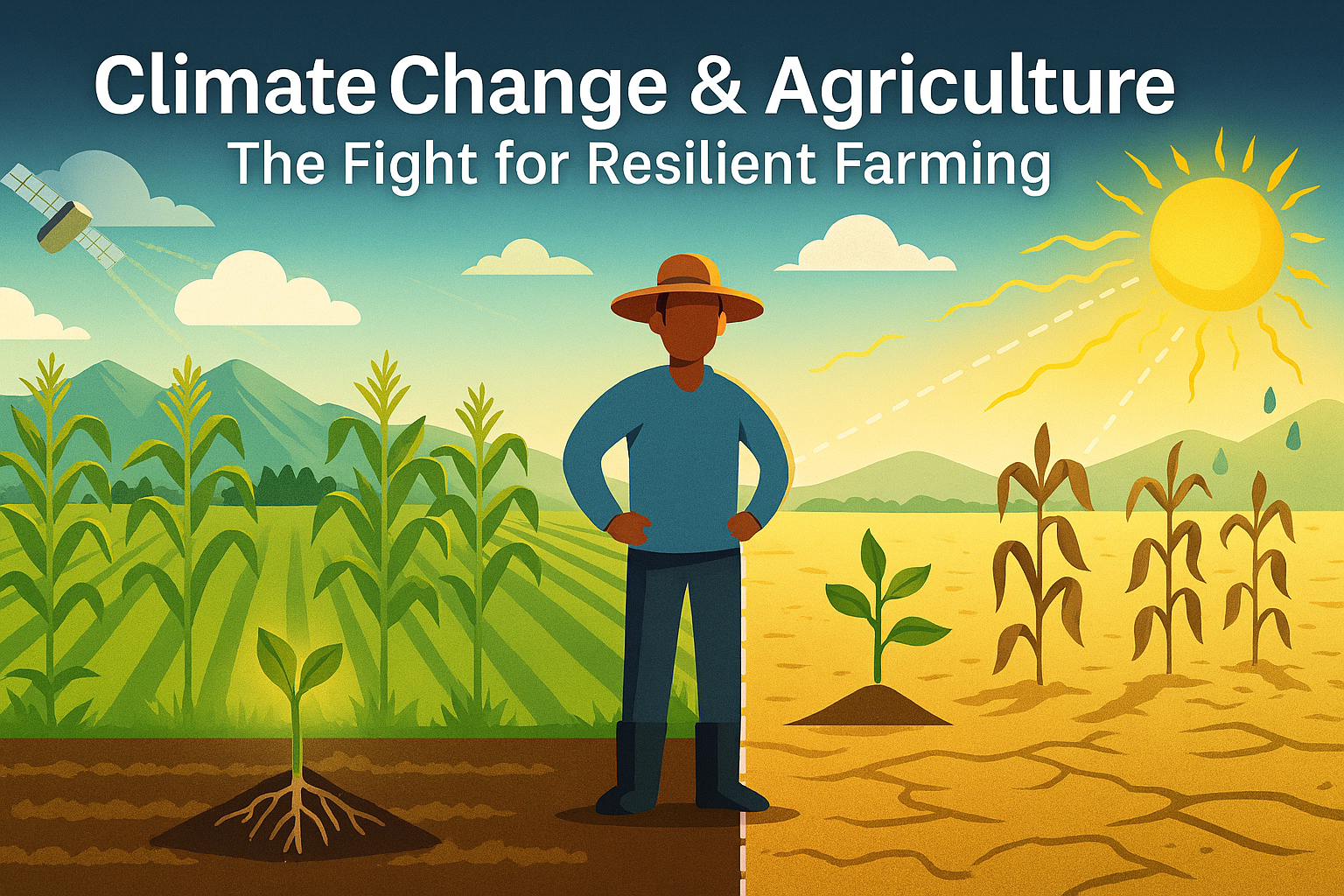

Farmers across the globe are confronting a harsh new reality: the climate crisis isn't coming—it's already here, and it's hitting their fields hard.

From Kenya's Rift Valley to America's Corn Belt, agricultural communities are grappling with unprecedented challenges. Pests that once stayed within known boundaries now march into new territories. Rainfall patterns that guided planting schedules for generations have become unreliable. Heat waves arrive earlier and linger longer. The result? Crop yields are falling at precisely the moment when the world's population continues to climb.

For growers watching their livelihoods hang in the balance, doing nothing isn't an option.

When Traditional Methods Meet Modern Crises

Michael Korir, who farms maize and vegetables outside Nakuru, describes the shift in stark terms. "Ten years ago, we knew when the rains would come. Now? We're guessing. And when we guess wrong, we lose everything."

His story echoes across continents. According to the research, agricultural productivity growth has slowed by roughly 21% since 1961 due to climate change impacts. That slowdown translates directly to food security concerns for billions of people.

Enter climate-smart agriculture (CSA)—a framework developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization designed to help farmers adapt to these new conditions while maintaining productivity and reducing environmental impact. The approach focuses on building resilience into farming systems rather than simply reacting to each crisis as it arrives.

Nature's Stress Relief: How Biostimulants Work

One tool gaining significant traction involves substances called biostimulants—products derived from natural sources that help plants withstand environmental stress without acting as fertilizers or pesticides.

Think of them as training supplements for crops. Just as athletes use certain nutrients to improve performance under pressure, biostimulants help plants cope with drought, extreme temperatures, and poor soil conditions. The science is straightforward: stressed plants require more inputs—more water, more fertilizer, more intervention—to produce acceptable yields. Each additional input carries environmental costs, from nitrogen runoff polluting waterways to the carbon emissions from manufacturing and transporting agricultural chemicals.

Plant physiologist study how these products function at the cellular level. They're seeing biostimulants that enhance root development in cold soil, allowing earlier planting and better establishment, while others trigger protective mechanisms in plants before heat waves or drought conditions strike.

The agricultural biotechnology sector has responded by developing targeted solutions for specific stress points in the growing cycle. Research published in Frontiers in Plant Science demonstrates that certain biostimulants can improve water use efficiency by up to 20% and enhance nutrient uptake under stress conditions, primarily by increasing photosynthesis, enhancing stomatal regulation to conserve water, and promoting antioxidant compounds for stress tolerance.

But there's a catch: timing matters enormously. These products work preventatively, not as emergency measures. Apply them after stress hits, and you've missed the window.

The Regulatory Minefield

Here's where things get complicated. Regulatory agencies struggle with how to classify biostimulants, particularly those containing plant growth regulators (PGRs)—substances that influence how plants develop.

The problem stems from history. Many synthetic PGRs were originally used as herbicides to suppress unwanted plant growth. As a result, regulatory bodies like the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Kenya's National Environment Management Authority tend to categorize anything affecting plant growth as a pesticide, regardless of whether it helps or harms the plant.

Karen Asinza, an agricultural policy consultant in Nairobi, describes the absurdity. "You can have a product made entirely from seaweed extract that helps maize tolerate drought. But if you mention it regulates growth—which it does—suddenly you're looking at pesticide regulations designed for toxic chemicals. The approval process can take years and cost hundreds of thousands of dollars."

The regulatory confusion has real consequences. Promising products sit in approval limbo while farmers need solutions now. Some manufacturers simply avoid PGR terminology altogether, even when accurate, to sidestep the classification issue.

Building a Better Framework

Agricultural scientists and industry groups are pushing for a distinct regulatory pathway for biostimulants—one that acknowledges their unique nature and lower risk profile compared to conventional pesticides.

The European Union has led on this front. In 2019, the EU established specific regulations for biostimulants, separating them from pesticides and fertilizers. Early results suggest the streamlined approval process is working, bringing more products to market without compromising safety standards.

Similar efforts are underway elsewhere. Plant growth regulators in African are advocating for harmonized standards across the continent, while American agricultural coalitions lobby Congress for clearer definitions and faster approvals.

"We need regulators who understand that a substance helping a plant survive drought is fundamentally different from one designed to kill weeds," argues Karen Asinza. "The science supports different regulatory approaches."

The Road Ahead

None of this happens in isolation. Climate-smart agriculture requires coordinated action—farmers adopting new practices, researchers developing better tools, policymakers creating sensible regulations, and companies investing in sustainable solutions.

The pressure is mounting. The World Bank estimates that climate change could push more than 100 million people into extreme poverty by 2030, with agricultural disruption playing a major role. Meanwhile, feeding a projected global population of nearly 10 billion by 2050 demands that we produce more food, not less.

Back in Nakuru, Michael Korir has started experimenting with biostimulants on a portion of his land. "I'm cautious," he says. "But I'm also realistic. Farming the way my father did won't work anymore. We have to adapt or quit."

That sentiment—adapt or quit—increasingly defines modern agriculture. The good news is that solutions exist. The challenge lies in making them accessible, affordable, and properly regulated before the climate crisis widens the gap between what we need to grow and what we can.